How the evolution of transportation opened Jekyll Island to the masses.

BY KATJA RIDDERBUSCH

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY MOSAIC, JEKYLL ISLAND MUSEUM

Andrea Marroquin has worked on Jekyll Island for more than 18 years, but she still gets chills when driving from the mainland over the causeway, across the bridge, and onto the island. The feeling grows as she passes marsh bunnies dotting the causeway, oak trees draped with Spanish moss, and the occasional deer on a stroll.

“As you travel onto Jekyll Island, you can picture the place and yourself back in time,” says Marroquin, a North Carolina native and curator of Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum.

Her life as a Glynn County resident, and her work studying and organizing the history of Jekyll Island, have taught her that transportation to and from the 5,950-acre Georgia barrier island over the centuries tells a larger story of the place and its inhabitants. It’s a story of chance, challenge, and change.

The history of Jekyll Island began some 3,500 years ago. Indigenous people, particularly the Guale and Timucua, inhabited the island before colonization. Artifacts and early European explorers’ writings suggest that the Native Americans moved among the islands and through the creeks in dugout canoes. To build them, they would cut large pine trees, “burn them out, shape them with stone tools, and paddle them across the waterways,” says Marroquin, who holds degrees in history and anthropology. The smaller canoes could hold two or three people, the larger ones up to 10.

When Spanish, French, and English explorers began to colonize North America, they came on big sailing ships but traveled the coast in smaller sailing vessels like yawls or bateaus, light, flat-bottomed boats.

Jekyll played a key role during the Colonial Era when General James Oglethorpe founded the colony of Georgia in 1733 and named the island after Sir Joseph Jekyll, a financial supporter. Oglethorpe later appointed Major William Horton to build a military outpost on Jekyll Island to protect Fort Frederica on St. Simons Island. “Jekyll was the southernmost extent of British territory, guarding against the Spanish,” says Marroquin.

The strategically important island became a bustling trade hub during Horton’s reign. He established a pre-industrial farm to supply Fort Frederica and neighboring barrier islands with beef and corn. Horton’s plantation also cultivated new and experimental crops like indigo, as well as barley and hops used to brew Georgia’s first beer. Most of the work was done by indentured servants.

Livestock and goods were shipped up and down the east coast on small sailing vessels. On Jekyll, roads were rough. People and freight moved by horse-pulled carriages, wagons, and carts.

Agricultural trade on Jekyll thrived until the Civil War, mainly due to the DuBignon family. French aristocrat Christophe DuBignon, fleeing the French Revolution, brought his family to Jekyll Island in 1792. They purchased land and developed a prosperous cotton plantation. During this era, sailing vessels gave way to more powerful steamboats. Ships traveled along the Intracoastal Waterway, says Buddy Sullivan, who has written more than 30 books and monographs about coastal Georgia.

“There was constant traffic of steamboats and barges transporting agricultural goods between the barrier islands and the markets on the mainland,” especially Charleston, Savannah, and Fernandina Beach in Florida, Sullivan says.

None of Jekyll’s success during the plantation era could have been accomplished without enslaved Africans working the fields and the docks. Most were purchased at mainland slave markets and brought to the island in small sailing or steam-powered ships, says Sullivan.

In November of 1858, 50 years after the slave trade was outlawed in the United States, Jekyll became the scene of a dark milestone in American history. It was then that the sailing vessel the Wanderer, originally built as a racing schooner and refitted to transport enslaved humans, landed on the island’s south end with about 400 slaves on board. The event marked one of the last known instances that a group of enslaved Africans landed in America.

Cotton production declined on Jekyll as the Civil War hampered the market and the soil on the island became exhausted. A decade after the War, DuBignon’s descendants inherited major portions of the island and purchased the rest. They turned the island into a luxurious retreat for the nation’s wealthy, launching the Club Era.

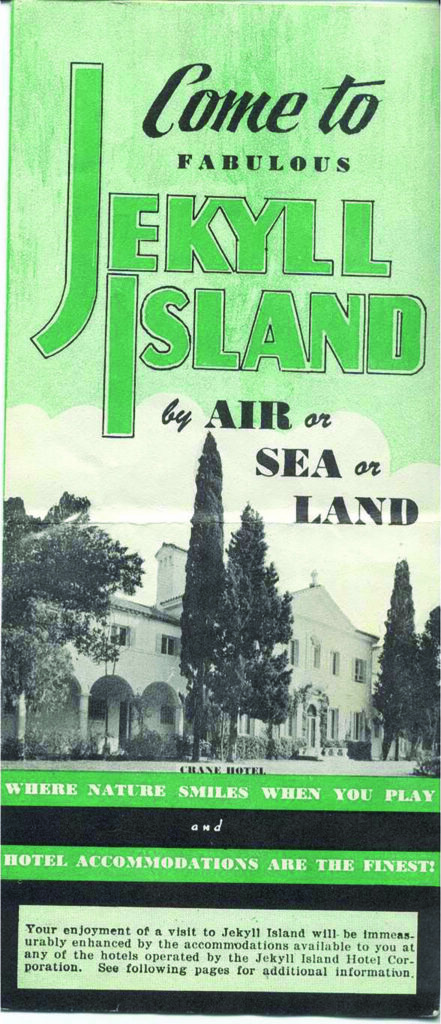

From 1886 to 1942, the Jekyll Island Club became one of the richest clubs in the world. Some of the world’s wealthiest people spent winters in the mild coastal climate, enjoying hunting, tennis, horseback riding, or beachfront golf. Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Pulitzers, Bakers, Goulds, Morgans, and Goodyears stayed at the elegant clubhouse or in their mansion-sized cottages.

Club members demanded exclusive means of transportation. Most arrived by train—often in private Pullman cars—at the Georgia port city of Brunswick, says historian Sullivan. “They would stay for a few days at the fancy Oglethorpe Hotel and then, at their leisure, come over to Jekyll Island,” either by small, steam-powered vessels operated by the club or on their yachts.

The island’s road network expanded during the Club Era. Members used Red Bug motorcars, little gas- or electric-powered buggies, to travel around the island, “sort of an early version of a golf cart,” Marroquin says.

The first automobile came by boat to Jekyll in 1900. While the rules for use were strict at first, automobiles became more popular by the 1920s, when many club members shipped their older cars to the island.

The millionaires’ Club Era ended when the U.S. government ordered the evacuation of Jekyll at the start of World War II. Georgia purchased the island in 1947, made it a state park, and later established the Jekyll Island Authority, the island’s governing body.

At that time, regular ferry service was introduced between the mainland and several Georgia barrier islands. To get Jekyll ready for public use, the authority landscaped the grounds and dug ditches for drainage, built motels, and paved a perimeter road. At least some of the manual labor was done by African American prisoners, shipped from the mainland and placed in a convict camp on the island.

Transportation to Jekyll changed dramatically shortly after that when, after six years of construction, the 6-mile causeway and drawbridge opened in December 1954, allowing more people to access the island by car. “They took the padlock off Georgia’s fabled Jekyll Island and threw away the key,” wrote The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in an article on the opening ceremony.

The causeway democratized the island, says Marroquin. “Jekyll became an island that belonged to the people. An island for everybody.”

In 1996, a taller concrete bridge replaced the drawbridge. Today, there’s also a small airport for private planes and a marina on the island’s south end. A bike path along the causeway eventually will allow people to ride bicycles from the mainland to the island, says Marroquin.

Yet with all the new and various means of transportation, with all the hotels, and with the echoes of the island’s illustrious and sometimes infamous past, Jekyll has managed to remain a low-key, casual place, preserving much of its natural state.

“And that’s exactly what makes Jekyll unique,” says Marroquin. And what still gives her chills whenever she crosses the causeway.