In a place so rich in history, the curators of the island’s past have to pick and choose which gems the public gets to see

By RICHARD ELDREDGE

Photography by GABRIEL HANWAY

The gleaming burgundy Studebaker parked inside Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum is like a magnet, gently

pulling visitors toward it to sit in its plush cream-colored seats. The vintage automobile serves as a distinctive pit stop for visitors, designed to give them an idea of what it felt like to drive across the Jekyll Island Causeway when it opened to the public on December 11, 1954.

“Everybody loves the Studebaker,” says Faith Plazarin, the museum’s archivist and records manager and self-professed history nerd. “We want guests to climb into it and have a good time. We want to make our history relevant to them.”

From pottery shards and tool fragments left behind by Native Americans (Jekyll Island’s original inhabitants) to the Studebaker and beyond, Mosaic has carefully preserved items covering thousands of years of island history. The pieces begin with the Native American finds and touch on the entire island timeline; Jekyll’s Colonial Era, its Plantation Era and the enslaved people who were a large part of the island’s past, the U.S. Civil War and its aftermath, the island’s famously glitzy Club Era, and into its birth as a state park. Debuting in Summer 2024, the museum will showcase an exhibition on Jekyll Island’s civil rights history, timed to the 60th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed by President Lyndon Johnson on July 2, 1964.

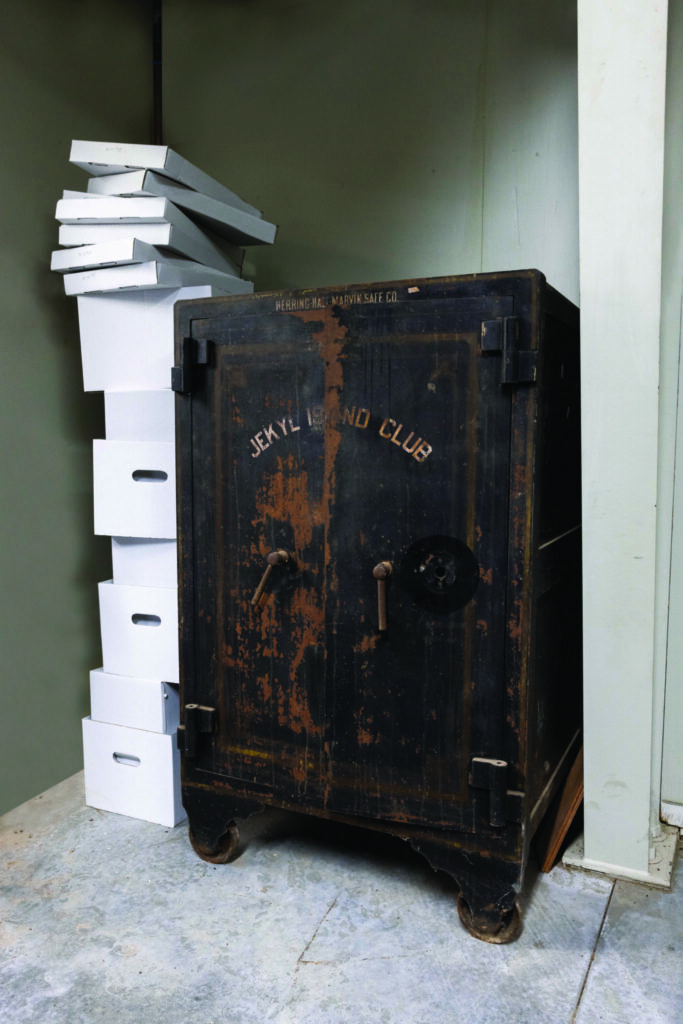

The collection provides a detailed look at the island’s past. The problem: There’s only so much room to store all that history.

With more than 4,300 of the island’s nearly 6,000 acres prohibited, by law, from being developed, the museum staff has to make use of limited archival space by being conscientious about what to keep and what to discard. Only a tiny fraction of the more than 6,000 objects, 16,000 images, and 21,000 archival records that are cataloged in the JIA database make it to public display on the island. Only about 200 of those items can be seen at Mosaic. (The archives can be accessed through research requests made via the Jekyll Island website.) “There’s never enough space,” says Plazarin. “But we do the best with what we have. Part of my job is to make sure we make space when we need it.”

All the historic items must be meticulously curated. Even items as simple as clothes hold the power to teach about the history of the island and to transfix the imagination. “There’s a ballgown and a wedding dress on display that are among my favorite pieces,” says Shalan Webb, the museum’s collections specialist. “I think they resonate with anyone who imagines playing dress up.”

Webb says she loves to observe families standing in front of the museum’s wardrobe exhibit, where interactive cameras “dress” guests in period costumes. “To hear that laughter, to see people getting excited about history,” she adds, “makes this work super rewarding for me.”

The stories told by these artifacts sometimes walk right in the front door of Mosaic and introduce themselves. Recently, a descendent of the famed Rockefeller clan that vacationed on Jekyll during the Club Era was cleaning out one of the family’s homes and unearthed some photographs. “It turns out, the photos were taken on the front porch of Indian Mound, the Rockefeller home here on the island,” Plazarin says, “and they were kind enough to bring them to us.”

Another example: When the grandniece of Bertha Baker, Jekyll Island’s first teacher (who served from 1901-1918), came looking for more information, she was shocked to discover that her grand-aunt was a Jekyll Island trailblazer. “She sat and gave us an oral history all about Bertha Baker and her family,” Plazarin says, “and gave us a better sense of what Baker was like.”

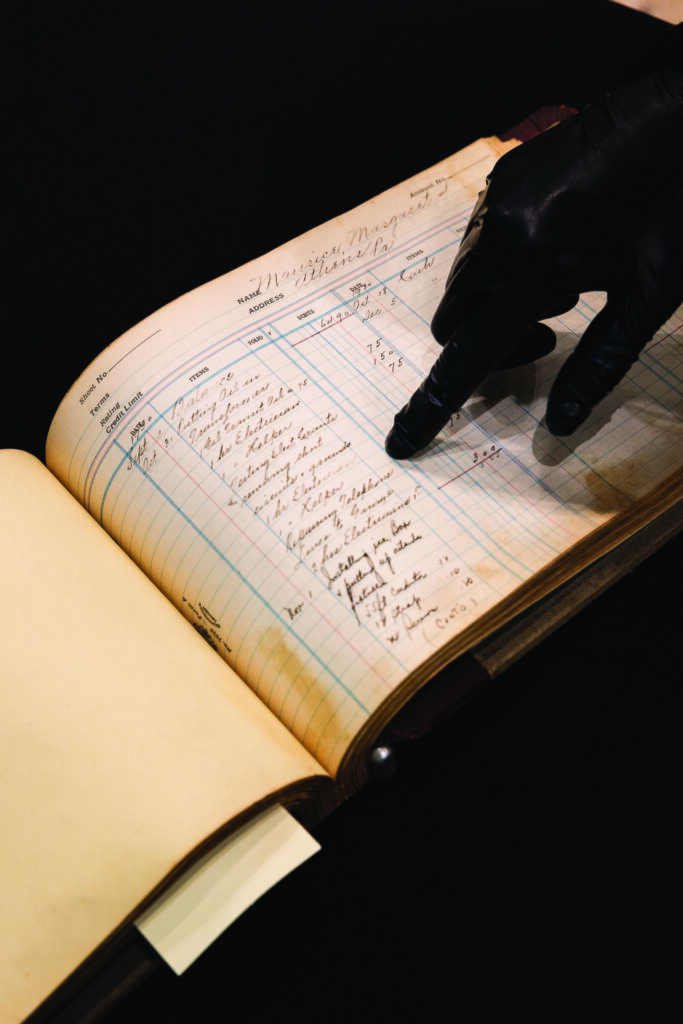

For Webb, donated treasures can take the form of something as common as a pair of little girls’ gray skirts. They were given to the museum by the granddaughter of industrialist Walter Jennings, who became a club member in 1927. “These two tattered, unraveling skirts look handmade and ordinary,” explains Webb. “But they were created by two children in the Jennings family during a chicken pox quarantine in 1938. Their governess kept them busy with lessons about the pilgrims coming to America and so they made these skirts … Collecting stories like this is my favorite part of the job.”

It helps, too, to be able to relate the island’s history to current events, like the hit HBO period drama The Gilded Age, which has reignited interest in the American industrial boom and the fabled “new money” families of the late 19th century. That era was the heyday of the very private Jekyll Island Club, once characterized as “the richest, the most exclusive and most inaccessible club in the world,” by Munsey’s Magazine. “The series has definitely exposed more people to the period,” Plazarin says, “and [showcases] why what we have here remains so relevant.”

Plazarin, who as an undergrad at Flagler College had a double major in History and English, says that digging daily through hundreds of years of papers is a dream job. “When I graduated, I knew I wanted a job where I could touch stuff,” she says with a laugh. “No day is ever the same here. I love when people walk in and say, ‘Hey, my great-granddad was a club member, do you have anything on him?’ I love that my job is often to play detective.”

The most prized treasures the museum has, in Plazarin’s eyes, are the island’s 1947 condemnation order and the subsequent Jekyll Island State Park Authority Act. “They’re not as cool as the pieces of furniture or the clothes,” she says, “but I’m an archivist. I love paper and those are the documents that allow us to exist.”

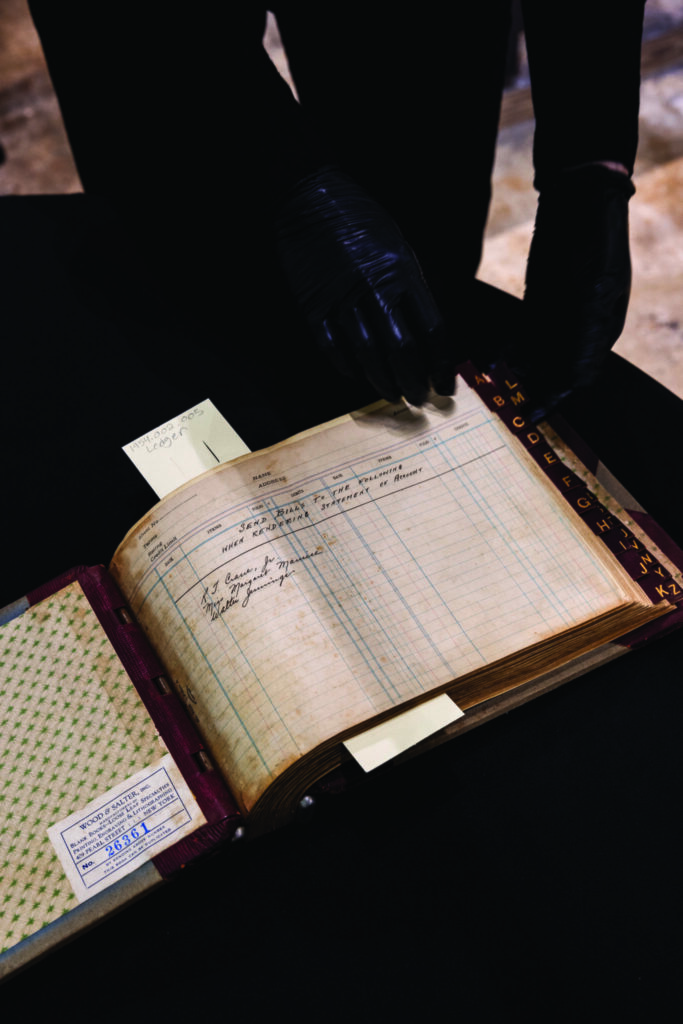

Both Webb and Plazarin agree that thumbing through the old club guest registers and seeing the names of wealthy members with last names like Rockefeller and Vanderbilt never gets old. “It’s rewarding not only to keep and preserve all these cool things but also being able to provide access to others,” Plazarin says. “That’s what makes this museum and Jekyll Island truly unique.”

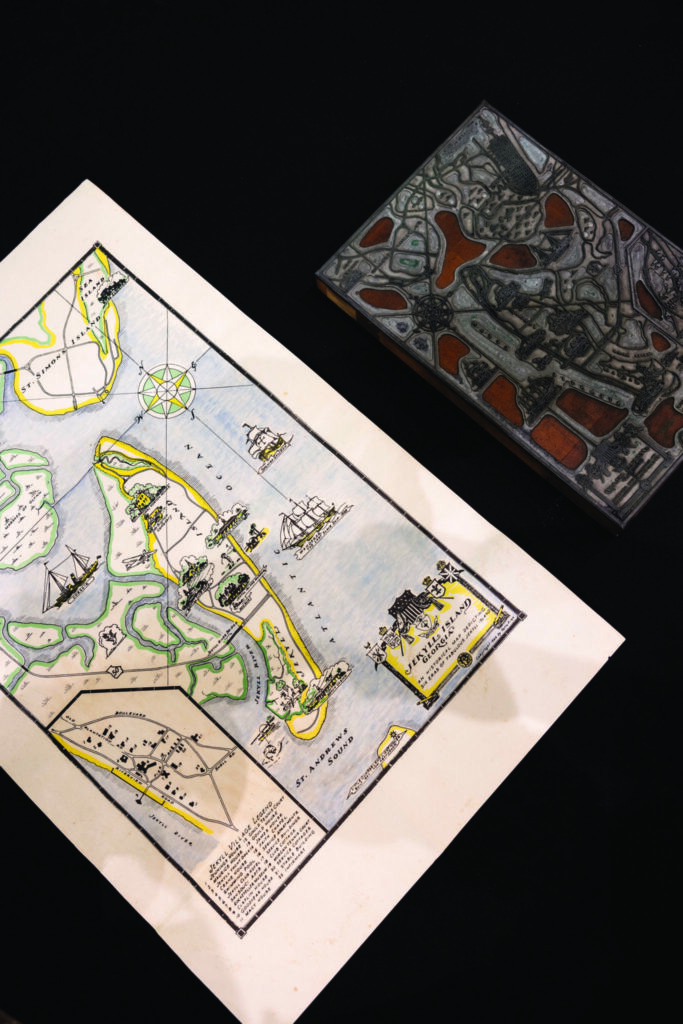

Only a fraction of the historic artifacts on Jekyll Island are available for public viewing. The following items were curated for this issue of 31•81 by JIA archivist Faith Plazarin and collections specialist Shalan Webb. They are not on public display.