Shortly after World War II, as the once opulent island lay nearly deserted, no one knew if Jekyll would survive

By Tony Rehagen

Modern Jekyll Island has always been synonymous with breathtaking beauty and indulgent relaxation. Whether through the Gilded Age opulence of the private Club Era or the more accessible family atmosphere of the State Era, the island has earned its reputation as a naturally stunning destination for those seeking to escape the workaday world on the mainland.

But there was a brief period, after World War II drained the vivacity out of the Club Era but before the state of Georgia breathed life back into the island, when Jekyll was a largely forgotten land. Abandoned by its wealthy patrons and not yet known among regular vacationers, Jekyll was a place overrun by wildlife and vegetation, where few but prison work crews ventured.

It was, in other words, 9-year-old John Dykes’s paradise.

“It was 200 percent different than it is today,” says Dykes. “We would just run around the island. We had a wonderful time.”

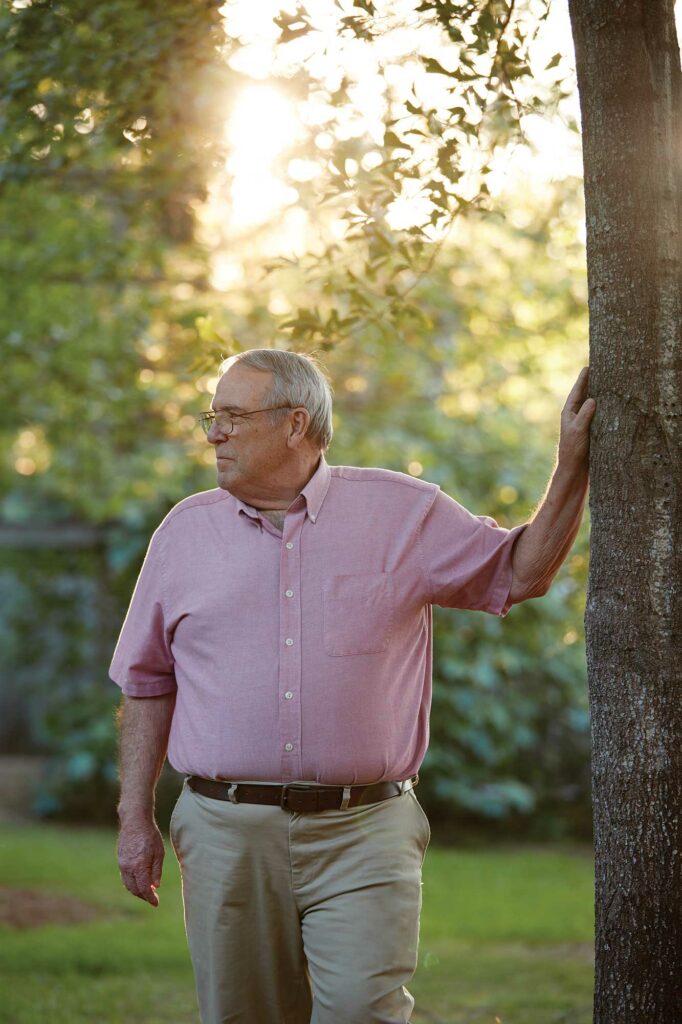

Dykes first came to the island in the summer of 1954, months before the causeway bridge was completed. The state had gained control of the island in 1947 through a condemnation decree, paying a mere $675,000 for it (or about $7.8 million in 2020 dollars), a bargain that has been compared to the purchase of Manhattan from the Native Americans. At the time, Jekyll had been largely closed to visitors while being prepared for public use. Dykes’s father, James Marion Dykes, a businessman and a member of the Georgia legislature from Cochran, had leased Sans Souci, the Crane Cottage, the Mistletoe Cottage, and the Jekyll Island Club’s Clubhouse from the state in hopes of opening them up for the tourists that were sure to come.

When young Dykes arrived that summer, his accommodations were far from luxe. He and his family were bunking in an old mansion with wardens of the convict camp that had been placed on Jekyll to do the manual labor of fixing the place up. The prisoners rebuilt roads where palmetto roots had blocked passage, installed drainage ditches, picked up trash and debris, and dug foundations for houses and motels.

Meanwhile, Dykes and his younger brother had their run of the island. They walked and biked everywhere. They went to the vacant beach to swim and cook clams from Clam Creek. They baited hooks with shrimp and fished croaker and sheepshead off the lone pier. They’d tag along with the game warden to watch turtles lay their eggs at night. And they explored the empty buildings that had been pillaged in search of their treasures.

The motherlode was the Jekyll Island Club, which had fallen on hard times since the breakout of World War II. The rich patrons had stopped coming, the local labor was drafted into military service, and the difficulty of operating during wartime forced its closing in 1942, effectively ending the Club Era. The owners had always intended to reopen, but the grand place was left waiting, frozen in time, for more than a decade. The doors remained unlocked.

Dykes and his younger brother rode the pull elevator up and down, stopping on each floor to roam the darkened halls. They dueled with fireplace-poker swords. In the basement, they found a room locked with chains but managed to squeeze through the double doors and find stacks of dinnerware and piles of silverware. Dykes still has a table knife with the Jekyll Island Club seal.

One day, Dykes and his brother found a ladder that led into the Clubhouse turret. There they found a naval flag and a club banner that had once flown high above the grounds; two more souvenirs to cherish.

The first Steps Back

The island opened to the public as a state park in 1948. The Jekyll Island Authority, established in 1950, focused its first efforts on getting the ocean side of the island ready for regular use, even as the Historic District sat in disrepair.

The causeway opened in 1954, making the island more accessible to curious vacationers. But Jekyll was far from an overnight tourist success.

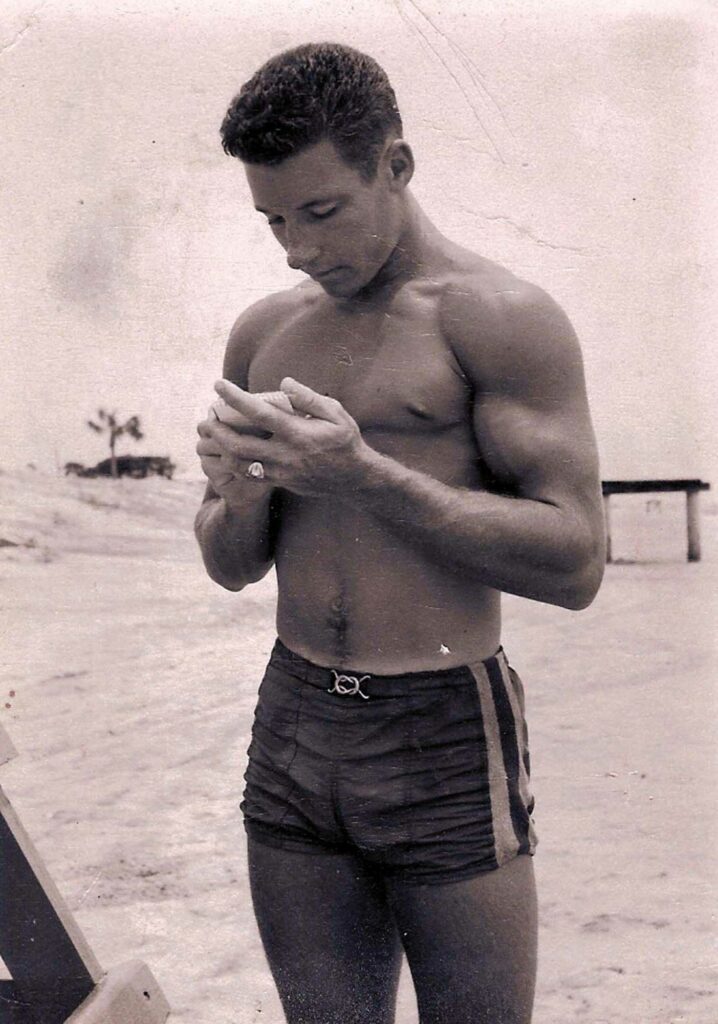

Mason Stewart was 16 in ’57 when he took a job as a lifeguard on Jekyll. In the summers, a truck would pick him up in Brunswick, along with other lifeguards, for their shifts monitoring a growing number of visitors staying at the Sam Snead Buccaneer Hotel (where the Hampton Inn & Suites currently stands), the Wanderer Motel (now the Holiday Inn Resort) or another of the new hotels up and down the coast. “All of the activity was on the beach,” says Stewart. “It was a very interesting time. There was no liquor on the island in those days and not a lot of nightlife other than the miniature golf course.”

In those days, the island belonged to the young, who came across the new causeway from the mainland. Stewart says there wasn’t a lot of drinking and partying going on, though he does happen to know that you can fit a surprising amount of vodka inside a plastic hula hoop.

But if you had a car, you could drive right up to the beach.

“On summer evenings, if you were a teenager, it was the beginning of the rock ‘n’ roll era,” he says. “You could lay out your beach blanket, turn your transistor radio to WAPE out of Jacksonville, and watch the sunset. Driftwood Beach was a secret that only us lovers knew about. We kept that to ourselves.”

The beauty of Jekyll would not remain a secret much longer. Under the guidance of the JIA, careful development along the ocean coast continued, while the island’s natural splendor was preserved. In the 1970s, the Authority turned its attention to the Historic District, renovating and rehabilitating the cottages and the Jekyll Island Club, which reopened as a luxury resort in 1985.

In recent years, the JIA has worked to connect Jekyll’s present to its past, setting up markers that detail island history all the way back to the Native Americans’ time. The history of the island is now delineated; the Colonial Era, Plantation Era, Club Era, State Era and today.

Some of the history lost during the Club and State periods is gradually returning to Jekyll. Furniture and other items from cottages are being replaced. And in 2019, Dykes donated the two flags he had found in the Jekyll Island Club turret to Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum. He had held on to them for 65 years.

“We visited the Club and walked around,” he says. “Everything has changed for the better. The credit goes to the people that were taking care of it and the people who promoted it. They’re doing what they can, and I’m proud of that.”

Bridging Club and State

Before the state of Georgia could pull Jekyll Island out of its “Forgotten Era” and open the isle to the masses, it first had to create a way for people to get there. Previously, the island was only accessible via boat—usually a yacht owned by one of the wealthy Club Era patrons. It wasn’t until 1954, seven years after the state acquired Jekyll, that the original drawbridge was completed, officially opening the Jekyll Island Causeway. That drawbridge was replaced in 1996 by the taller concrete bridge that stands today.